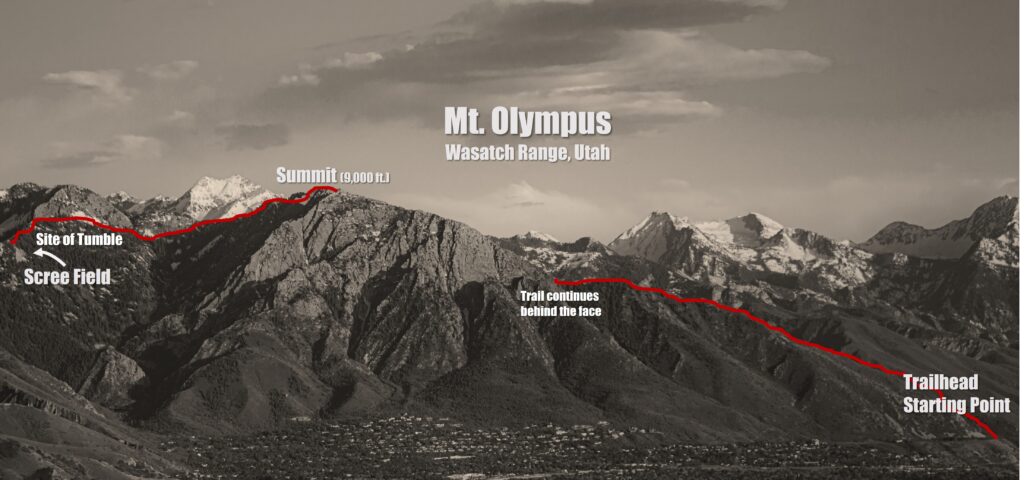

This is the second of five posts highlighting lessons learned from a hiking accident on November 3, 2020. This week’s lesson: Living in Reality.

Get Real

As I lay there on the rocks, unable to stand, I brought my hands up to feel my head and determine whether I really had cracked my skull. I felt a significant amount of bleeding and a deep divot in my scalp. It was very dark—my headlamp had flown off within the first few moments of my tumble. I didn’t know where my friends were because they’d rounded the ridgeline in front of me before I fell. I thought I could hear them calling me, so I tried to call out to them. All I could muster was a sort of garbled moan.

I knew I needed to stop the bleeding somehow, so I pulled the front of my sweatshirt up over my head and applied direct pressure.

Where’s Stu?

Moments after I’d fallen, my friends realized I wasn’t behind them and began calling for me but heard no response. They retraced their steps and continued calling. They covered their headlamps and scanned the area for any light, then noticed a glow at the top of the scree field. There, they found my headlamp and my hat on the rocks. They quickly put two and two together and began looking down the fall line for me. They carefully made their way down the steep pitch, trying to avoid pushing any rocks down as they went. That’s when, in the light of their headlamps, they began to see something tangled up in a dead tree about a hundred feet away. One of my friends later confided in me that when he first saw me, he thought I was dead.

Coming to Grips with Gravity

To the relief of my friends, when they reached me, I was awake and coherent enough to talk through my injuries with them. In addition to being generally beaten up, I had several large lacerations on my head. These were most immediately concerning because I take a prescription anti-coagulant. My left arm couldn’t bear any weight, so I assumed it was broken. I could also feel blood on my left shin from a large V-shaped gash which we soon discovered went to the bone.

In those first few moments, each one of us had to come to grips with the gravity of the situation. As we processed the overwhelming details of the moment, we oscillated back and forth between the best and worst possible cases. But soon we collectively settled on the same conclusion. Given the time of day, the challenging terrain, and the nature and extent of my injuries, there was no chance I was getting off the hill without emergency help.

The Lesson: Resilient Organizations Live in Reality

Like many organizations, when things change in our environments, our first inclination is often to ignore the change or assume it’s not that bad. This classic state of denial is a defense mechanism we all use to avoid the pain of adaptation. However, when we stay in denial, we lose much of the time we could have spent adapting to the new environment. The sooner we begin adapting to change, the sooner we can realign our identities to match new circumstances (see Lesson #1).

In a recent HBR article, Scott Edinger points out that accepting our circumstances liberates us. He says: “acceptance gives you power to move forward in the most effective way possible instead of waging a futile battle against circumstances you can’t control.“

On the mountain, if my friends and I had downplayed the seriousness of my injuries or kept trying to follow my initial impulse to stand up, we certainly would have wasted invaluable time. In fact, moving me could have been life-threatening due to more significant injuries none of us were aware of at the time.

Unfortunately, history is filled with examples of leaders and organizations who refused to live in reality. Leaders often surround themselves with people who tell them what they want to hear, mostly that everything is fine. The people in their inner circle may even share that false reality, or they may prefer to avoid the discomfort of telling the king they have no clothes. This they do at their own peril.

Mulally’s Push for Reality

In contrast, I recall a story told by Alan Mulally when he took over as the CEO of Ford Motor Company in 2006. During his first few months in the role, he implemented a process of weekly business review meetings in which the top business and department heads shared the statuses of their various groups. Ford was expected to lose over $17B in that fiscal year. However, as the review meetings progressed, each week the presenters continued to indicate that everything was going fine in their respective groups.

Finally, after several weeks and some cajoling from Mr. Mulally, a courageous leader brought a significant issue to the table regarding a production problem. Mulally began applauding in the meeting then simply asked if there was anything he could do to help? That was the beginning of a new culture of transparency, collaboration, and living in reality which helped Ford work its way back to profitability.

Insist on the Truth

Leaders of resilient organizations are obsessive about living in the truth. Leaders set the example by building close relationships with anyone who can keep them in touch with reality. That includes their customers, their suppliers, their competitors, their industries at large, the communities where they operate, and yes, even and especially their own people. Resilient organizations constantly watch for patterns and trends in and out of their organizations. They utilize data to objectively confirm what’s really going on. Resilient organizational leaders unflinchingly face the truth and encourage, even insist, that everyone around them do the same.

Next week: There is no down, only up – defining the new objective.

If you’re interested in learning more about organizational resilience, or Ferron Creek consulting, please contact me at stuart.larson@ferroncreek.com. We’d love to see what we can do for your organization!

Comments are closed