This is the final of five posts highlighting lessons learned from a hiking accident on November 3, 2020. This week’s lesson: The Power of Unified Diversity.

As the sound of the helicopter grew louder, my friends quickly extinguished the small fire to prevent it from getting whipped up by the blades. The pilot made a few passes to evaluate our position, then lowered a rescuer down to us on a cable. The rescuer untethered himself and the chopper rose to a higher altitude.

He quickly assessed the situation and unloaded a rescue seat that would slide under my body and clip back onto the cable to be hoisted up. He also wrapped a rolled bandage around my head, enabling me to bring my hands down after nearly two and a half hours. With the help of my friends, he slid the harness underneath me then called the chopper back and attached the cable. While the chopper hovered, the hoist operator slowly lifted me off the hill.

The rescuer on the ground was wearing a GoPro camera on his helmet and recorded much of the event.

I remember how loud and windy it was as I approached the chopper. When I finally reached the open door, I was surprised when the rescuer inside left me hanging outside. It was too noisy to say or hear anything. But I remember him keeping his hand on my shoulder as he released the rope attached to the back of the harness dropping it to the ground. He kept his hand on my shoulder patting me on occasion to reassure me as the pilot carefully flew down the canyon.

Finally On the Ground

We landed in a staging area at a parking lot of a nearby middle school. Once we were on the ground, several first-responders carefully lowered me directly onto a gurney. Thankfully, they determined that my condition didn’t warrant a second chopper flight to the hospital. Instead, they loaded me into a waiting ambulance and rushed me to the University of Utah Medical Center. While we were en route, one of the paramedics asked me for more details about my accident. When I told him I had tumbled about 100 feet down a scree field, he looked at his partner and raised his eyebrows. They carefully put a neck brace on me.

Upon arriving at the hospital, the paramedics quickly wheeled me into the trauma center where a team of doctors, nurses, and technicians descended on me. The paramedics rattled off the list of known injuries. Then the doctors began asking me more questions as they cut off my clothes and began taking my vitals. I was mostly coherent through the experience. Although, at one point I asked if they could give me something to knock me out, but they said they wanted me awake. So they gave me some painkillers and kept talking to me.

1-2-3-Lift!

Because of the possibility of a broken neck, when I was moved from the gurney to the examining table, and subsequently on and off various scanning beds through the night, it took at least 5 people to do it; two or three on each side, and one person who was dedicated to keeping my head perfectly stable. With each change of table, one team member would count to three, then everyone lifted and moved me in one unified motion.

The next several hours are a blur. I recall fragments of conversations, being wheeled to different rooms, and spending an inordinate amount of the night with a drape over my head as the plastic surgeon sewed my head back together.

It Takes a Team

I don’t know exactly how many people were involved in my rescue and treatment that night. If you count my two friends, the dispatchers, the two ground teams (who never made it to us), the chopper rescue crew, the paramedics and police at the staging area, plus the trauma team and hospital staff; I estimate that it must have been somewhere between 50-75 people. Each one played a part in helping me that night. Besides being filled with gratitude for their courage, dedication, and expertise, I gained a new appreciation for the power of a diverse group of people with a common purpose.

The Lesson: Resilient Organizations Harness the Power of Unified Diversity

One of the most important resources leaders can build to increase resilience in their organization is diversity of thought, perspective, and experience within their teams. On the mountain, I witnessed how each person involved added something new to the mix. Similarly, leaders expand the breadth of new ideas and innovation when they expand the diversity of their people.

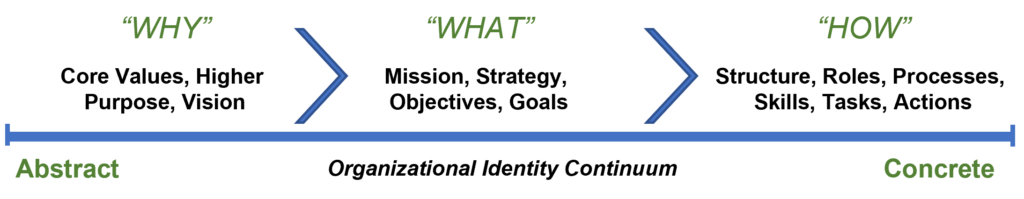

But the presence of diverse people and ideas alone is not enough. Clever improvisation requires that two seemingly paradoxical factors are present: The group must be as diverse as possible while being as unified as possible. This conundrum can be solved by applying the identity continuum introduced in Lesson #1.

To bridge this paradox, a leader must create a common, shared sense of deep identity. They do this by focusing first on the left end of the continuum which means evangelizing the organization to a common purpose, values, and/or vision (see Lesson #1). Then, the leaders must also create common objectives (see Lesson #3), and empower their teams with all the resources necessary to innovate (see Lesson #4). At the same time, leaders must find, support, and leverage as much diversity as possible within their teams as they cleverly improvise answers to all of the how questions on the right end of the continuum.

Global Diversity Unified by a Common Purpose

As an example; when I worked for a large agricultural biotech firm, the unifying purpose was very clear: Feed the world’s growing population using fewer natural resources through bleeding-edge science. This was a truly global organization with members from practically every corner of the world. And, although we weren’t perfect, we worked very hard to include, value, and leverage every voice who came to work for the company.

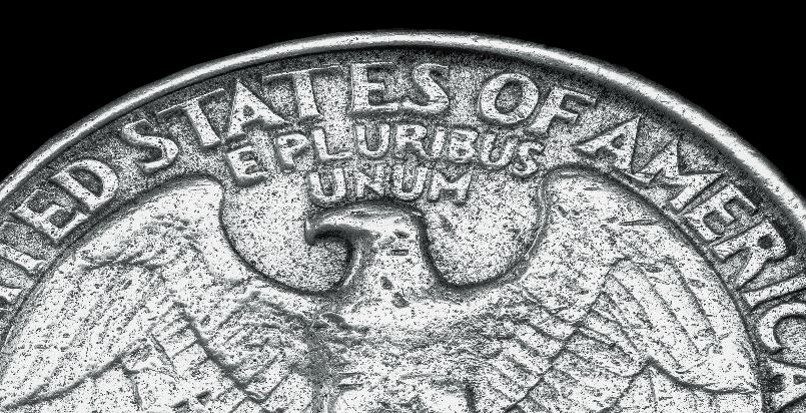

But diversity alone wasn’t what made the organization resilient; it was the shared deep identity that united the diversity which made the organization powerful! There’s great wisdom in the motto of the United States: E Pluribus Unum; out of many, one. When diverse people unite, they become powerfully resilient!

Epilogue

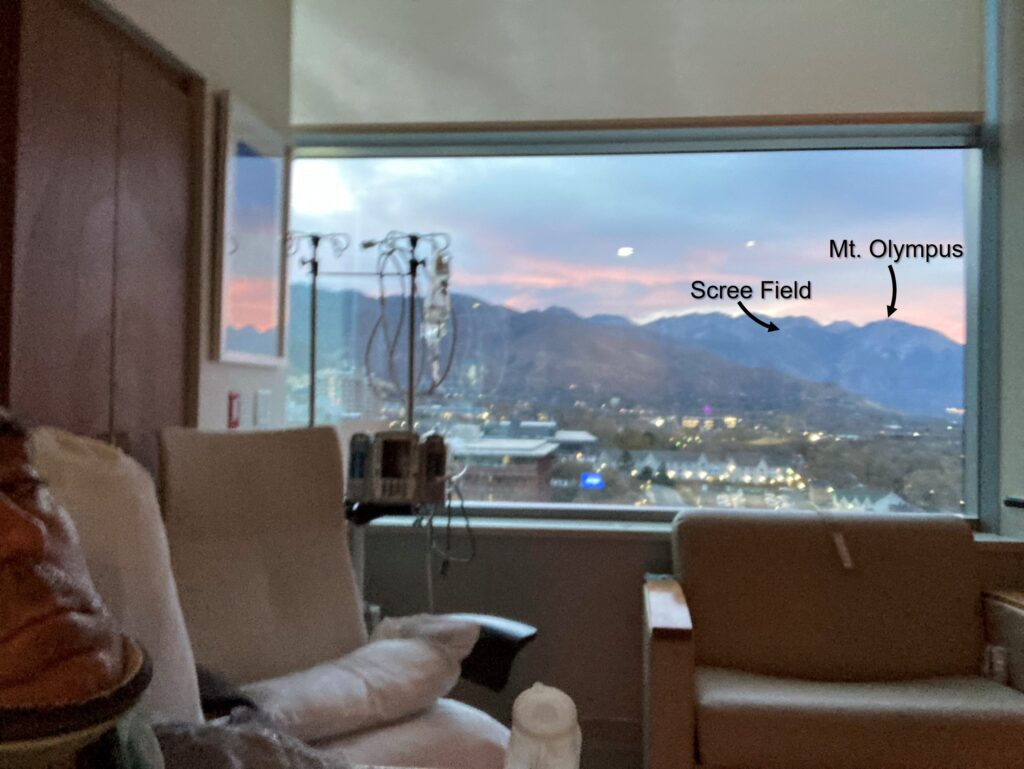

After eight-plus hours in the trauma unit, 24 hours in a surgical ICU, and two days in a regular hospital room, remembering how to stand, walk and use the restroom again, I was allowed to go home. (My hospital room, ironically, looked south toward the mountains so that I could literally see the spot where I fell.)

My list of injuries was not insignificant, but it could have been much worse! As it was, I suffered severe lacerations to my head and leg, a broken humorous near my shoulder, and a cracked cheekbone. And (unknown to any of us on the mountain) I also suffered a broken neck at C2 and C7 with multiple compression fractions in my lower back. The fact that I am still alive and not paralyzed today is truly a miracle.

The divot I felt in my head, wasn’t a broken skull after all, but just a wide tear in my scalp. The plastic surgeon sutured the wound together as much as possible in the trauma unit. But, I was still missing a chunk of skin up there. Thankfully, with time, the head wounds have healed and filled in with hair.

I’ve had a long road to recovery. But after a year of follow-up visits and physical therapy, other than some gnarly scars, I’m basically back to where I was before the accident.

Resilience

However, I’ve learned a few lessons which I won’t soon forget. Including the fact that you never know when your life may change dramatically. Whether as an individual or as part of a team, organization, community, or nation, things can change quickly whether we expect them to or not. In fact, it seems that the quantity and complexity of the challenges we face these days only continue to grow. Resilience may indeed be the most important quality of any organization in our age.

Leaders and organizational members who can learn to:

- Establish a strong sense of deep identity,

- Live in reality,

- Quickly define and organize around new objectives,

- Empower clever improvisations, and

- Leverage the power of unified diversity,

may not only increase their chances of surviving the unexpected but may come through stronger and healthier than ever before.

Final Thought

I would be remiss if I didn’t express my sincere gratitude to all of the people who helped me that night; most of whose names I don’t know. I’m particularly grateful to the Salt Lake County Search and Rescue Team and my two great friends Steve and Justin Wilson. Although they share the same last name they are not literal brothers, but they will forever be brothers to me.

If you would like to learn more about the organizational identity continuum, organizational resilience, building stronger leaders and teams, creating healthier cultures, or Ferron Creek consulting in general, please contact me at [email protected].

Comments are closed