This is the third of five posts highlighting lessons learned from a hiking accident on November 3, 2020. This week’s lesson: Defining New Objectives

Given my injuries and general inability to stand up, let alone walk, we realized we had to call for help. We called 911 and, thanks to our proximity to the valley, we were soon connected with the dispatcher for the Salt Lake County Sherriff’s Search and Rescue team.

The dispatcher and my friends talked quickly to assess the seriousness of the situation. The dispatcher also used our cell phones to locate us on the mountain. Almost immediately, they called in two ground teams to try and reach us on foot. But, given the steep and rugged terrain, the density of the brush, and the absence of trails in that area, the ground teams faced a daunting task.

Ultimately, the dispatcher asked if they could get a visual of my injuries. My friends helped me take my hands and sweatshirt off my head long enough to take some pictures. They documented the grizzly lacerations on the top and sides of my head and on my leg. Then I quickly put my hands back up to keep pressure on the wounds. Worst of all, I was starting to go into shock, trembling uncontrollably.

The Best Way Down is Up

After the pictures of my injuries came through, the search and rescue commander decided it was time to call up the helicopter rescue team.

Everyone involved shared one clear purpose: Safely get me off the mountain as soon as possible. We also shared a clear new strategy – the fastest way down was to go up. Once everyone involved understood the new direction, it liberated us to focus our collective attention on that goal.

The Lesson: Resilient Organizations Quickly Define New Objectives

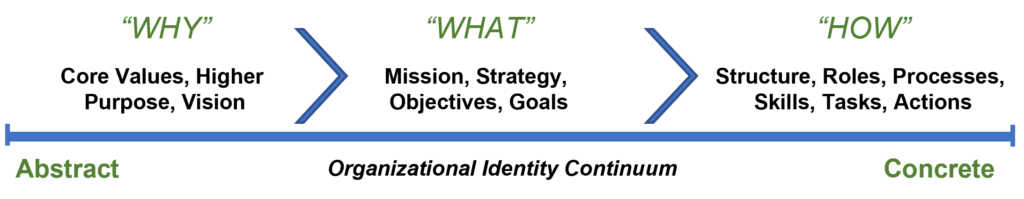

Once an organization’s leaders come to grips with a new reality, they must quickly identify new objectives. This new goal should be based on their deeper bedrock purpose (the why). With their new objective clear (the what), organizational members can begin to figure out how to achieve the goal. They do this by redefining the work to be done on the right side of the identity continuum. (See below).

Many leaders fail in this principle in two ways:

Mistake #1: Not Committing and Communicating Quickly Enough

When the world turns upside down, some leaders fail to create clear new objectives because:

- They are afraid to commit resources.

- They may be waiting for the environment to stabilize, or for more validation that things have really changed as much as it seems.

- Or, they may simply want to keep their options open for as long as possible.

Although there’s some wisdom in not leaping too soon, many leaders fail by waiting too long, or never leaping at all! Some theorists, like Karl Weick, argue that it’s only through taking action that organizations can figure out what needs to be done next.

Even if leaders set a new target, they may also fail to effectively communicate it to the organization. In either case of not committing or not communicating, organizational members don’t know where the organization is heading, and valuable time and energy are wasted waiting for clarity.

Mistake #2: Micro-managing the Details

Other leaders fail by trying to define every aspect of the new direction themselves. They erroneously believe that only they can determine all the elements of the path forward. They fail to empower their teams to create clever, innovative ways to achieve the superordinate goal. I’ll share more about this principle next week.

Kennedy’s Bold New Direction

When President John F. Kennedy announced in September 1962, “We choose to go to the moon” he was declaring to the American people, a clear objective in the face of a series of setbacks in the space race. No longer was the goal simply to get a man into orbit, which the Russians had just accomplished, the goal now was to land a man on the moon and safely bring them home.

Kennedy didn’t equivocate on the objective, and he didn’t hesitate to declare it. He shared his vision with congress only a month after the Soviets had successfully sent Yuri Gagarin into space. And he didn’t attempt to articulate every detail – many of the tools, and technologies needed to achieve the goal hadn’t been invented yet. But I believe he understood that the US needed to re-orient its collective attention to a higher goal without which the US would continue to lose to the Russians in space.

From his speech at Rice University, Kennedy said:

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade, not because [it is} easy, but because [it is] hard – because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills – because that challenge is one we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win.”

When things start to go downhill, resilient leaders live in reality (see Lesson #2). They quickly assess what can and needs to be done based on their deepest sense of identity and purpose (see Lesson #1). They make a decision, then quickly focus their teams on new, clear, and compelling objectives. Then, they empower them to make it happen and get out of the way.

Next Week: Clever improvisation on the side of a mountain

If you’re interested in learning more about building stronger leaders, or Ferron Creek consulting, please contact me at stuart.larson@ferroncreek.com. We’d love to see what we can do for your organization!

Comments are closed